Click here to view or download a PDF.

Click here to view or download a PDF.

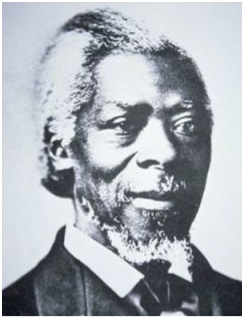

William Lambert was born in Trenton, New Jersey in 1817, the son of a freed father and a freeborn mother. As a young man, he was educated by abolitionist Quakers. He arrived in Detroit, Michigan in 1840 as a cabin boy on a steamboat, and eventually started a profitable tailoring and dry cleaning business.

In Detroit, Lambert soon became active in the movement to secure the right to vote for the black men of Michigan. He founded the Colored Vigilant Committee, Detroit’s first civil rights organization. In 1843 Lambert helped to organize the first State Convention of Colored Citizens in Michigan. He was subsequently elected chair of the convention and gave an address regarding the right to vote that was directed not only towards black people, but also to the white male citizens of the state. Lambert also worked to bring public education to the black children of Detroit.

Lambert was a friend of radical abolitionist John Brown and, like the more militant abolitionist leader Henry Highland Garnet, Lambert called for the slaves to rise up against their owners.

At times Lambert very publicly helped fugitive slaves escape to Windsor, Canada. His most famous incident occurred in 1847, when he had the owner of fugitive slave Robert Cromwell thrown in jail so that Cromwell could escape to Canada by boat.

Much of Lambert’s abolitionist work, however, was done behind closed doors. Unlike the abolitionist movements that emerged in other Northern states, African Americans were excluded from Detroit’s Anti-slavery Society. Lambert later claimed to be the creator and president of the secret organization, African-American Mysteries: Order of the Men of Oppression.

In 1885, two decades after the end of slavery, he shared his story with the Detroit Tribune, and produced documents, including lists of transported slaves and correspondence with John Brown, Lucretia Mott, Wendell Phillips, and William Lloyd Garrison.

The Order kept few physical records, and outside of Lambert’s and several other accounts, most of the evidence of its existence comes in the form of rumor and cryptic asides in the journals of white abolitionists. The Order was nearly exclusively African American in composition. Only a few white men rose past its lowest levels. The Order had secret words, grips, rites, and solemnities, all of which were designed to prevent the uninitiated from receiving the higher knowledge that came with ascension, i.e., practical information pertaining to the business of their efforts to help black men and women escape from slavery in the United States. Lambert claimed that, in its heyday, the Order transported 1,600 slaves to their freedom per year, moving people through their network of homes and barns from the Ohio River to Lake Erie in ten days. While that number may be an exaggeration, there is little doubt that this secret organization helped fugitive slaves flee to Canada.

Lambert was also a founder of the St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church and served as one of its wardens.

William Lambert died on April 28, 1890, at the age of 73. He is buried in Section G, Lot 90. His monument is pictured below. Upon his death, Lambert left behind an estate estimated at $100,000.

Lambert is listed in Elmwood’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Self-Guided Tour Map.

This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), funded by the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in the material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASALH or the Department of the Interior. Elmwood Cemetery’s Network to Freedom Application was completed by Carol Mull and Gabrielle Lucci. This biography was completed based upon the Application and records available through Elmwood Cemetery, Detroit Historical Society, Burton Historical Library, Military Records of the United States, Michigan Historical Center, and various information sources.